Face-to-face spoken interaction is arguably the most fundamental and efficient form of human communication, difficult to replace with anything else. In today’s world, we can satisfy many of our pure information transactional needs using touch screens and keyboards – or indeed by voice. Currently, we see a surge in voice-based technologies deployed on smart speakers, in cars and on our mobile phones. Disembodied voice assistants work well for short query and command/control style interactions, but in more complex or demanding scenarios (education, elderly care, simulation, training and entertainment) these simple voice-only interactions will fall short.

Similarly, there are certain conversations that we would rather have face-to-face rather than over the phone or via email. Not even video is good enough in many cases – we still often prefer to meet someone face-to-face, if we have the possibility to do so. Why is this? Information-wise, it is perfectly possible to express everything in text form, isn’t it? The main reason is of course that a lot of the information in face-to-face interaction is non-verbal, i.e. anything that we don’t express using words but rather by gestures, facial expressions and eye gaze, intonation and so on. These tell us about attitude, emotion and attention. They help regulate the taking of turns in a dialogue or in a group conversation. They contribute to the engagement, intimacy, attention and robustness in the interaction.

When such non-verbal cues aren’t available, we get robbed of part of the message, which can lead to confusion or even breakdown of the communication (this is also why we use emojis, e.g. when texting).

At Furhat Robotics, our dream is to make interaction with robots as smooth and effortless as a well-paced face-to-face interaction with your best friend. And this means that we need robots to be able to produce all the visual and spatial cues that go along with speech (and more).

But non-verbal communication isn’t the full story here. There is even more information in the face, that in some situations can be downright crucial to the understanding of the spoken content. I’m talking about lip movements. When humans speak, we move our lips, jaw and tongue in a highly complex and carefully orchestrated pattern. This is just an unavoidable consequence of how we produce speech. But these movements also form a very distinct visual pattern that humans have learnt to decipher surprisingly well. That’s why we can easily spot if there is a lag between sound and image in a video clip or if a movie is dubbed.

The visual perception can also directly change what we actually hear: If the video of a speaker saying “ga” is paired with audio “ba”, many people will perceive the result as “da” because the brain will try to find a speech segment that matches both the visual and auditory percepts optimally. This is known as the McGurk-effect and was described in the famous 1974 article “Hearing Lips and Seeing voices” by Harry McGurk and John MacDonald.

But visual speech is more than just an effect: watching the lips move will indeed help us understand what is being said. And no, you don’t need to be a specially trained lip reader to benefit.

While it is true that “pure” lipreading without sound is very challenging, it is also true that most people will understand less of a message when they only hear the voice than when they also see the face, especially if they are in a bad acoustic environment.

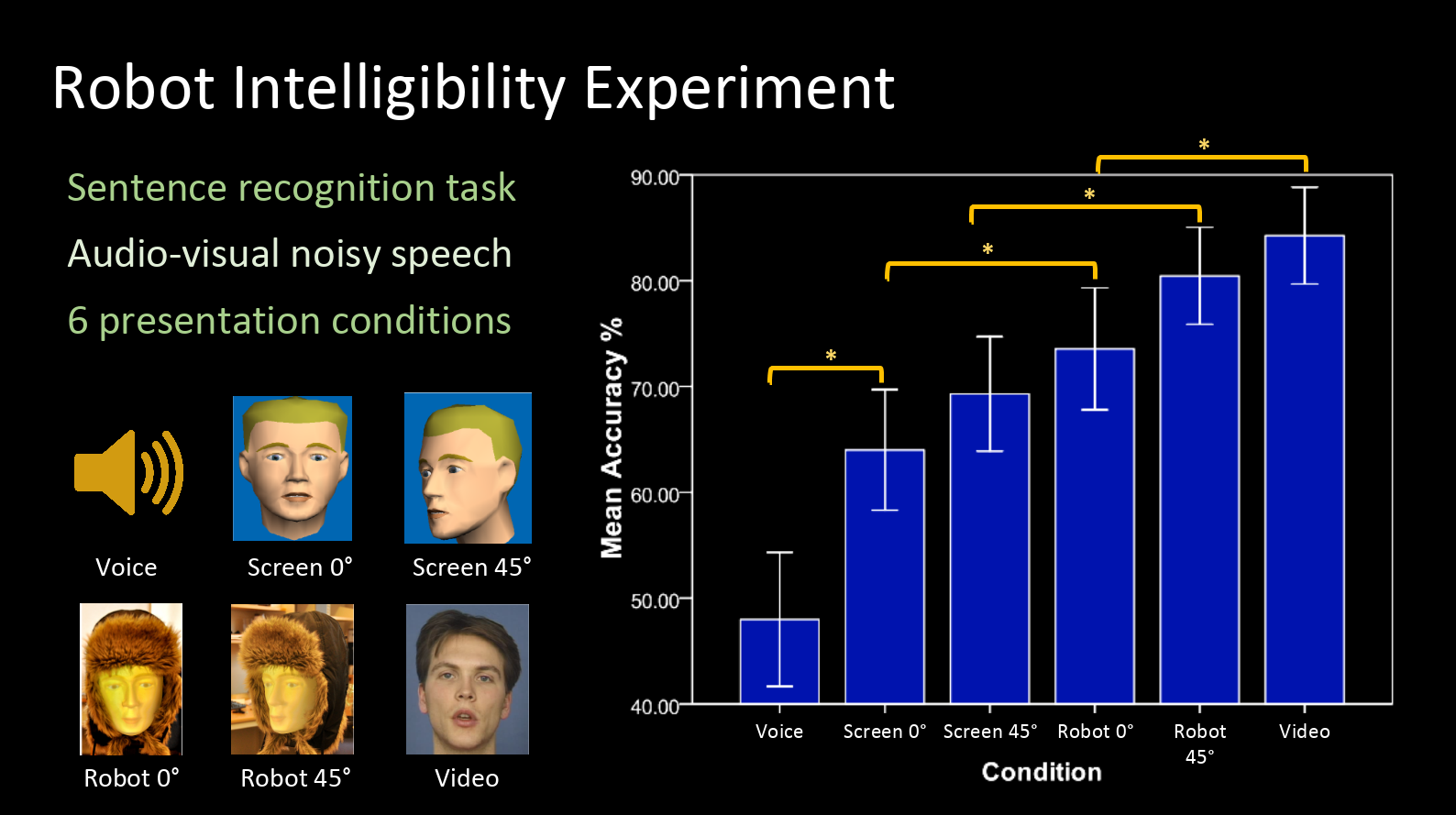

And this translates very well to animated faces. In an experiment, we simulated such poor acoustic conditions by degrading a set of clearly articulated sentences, and asked people to repeat what they heard and measured how many words they would get right, under several visual conditions:

- Audio only

- Animated face on a screen

- Video of real talker’s face on a screen

- Furhat robot with back-projected animated face

Additionally, the animated on-screen face and the robot were presented at two different angles: straight on (0°) and at 45°, as can be seen in the image below.

The image shows the results of the experiment in terms of mean accuracy (percent correctly recognized words) per each condition. It can be seen that the audiovisual intelligibility of the Furhat back-projected face was significantly better than that of the audio only condition as well as the screen-based animated face – it was only surpassed by the video of the real talker. (Significant differences are marked with an asterisk * in the image above). To be noted here is the fact that the face displayed on the screen was identical to that being projected onto the plastic mask of the physical robot.

The findings were a little puzzling to us at first, but the result is indeed in line with findings in recent literature, showing that people have a stronger behavioural and attitudinal response towards a physically embodied agent than a virtual one, which means that the physical presence of the robot face in the same space as the user plays an important role.

Knowing that seeing the lip movements helped people understand speech, we were curious to see if motion in other parts of the face would be able to further increase intelligibility of the speech signal. In particular we decided to investigate whether eyebrow- and head motion could affect how well we perceive speech from an animated face or a robot. We conducted a speech intelligibility experiment, where short read sentences were acoustically degraded in the same way as in the previous experiment. The speech was presented to 12 subjects through an animated head carrying head-nods and/or eyebrows-raising gestures, that were spread out over the utterance in a way that matched the spoken realization. The experiment showed that these face/head gestures significantly increased speech intelligibility compared to when these non-verbal gestures were either absent or are added at randomly selected syllables. This pattern of movements (based on acoustic prominent syllables) is now the default method of generating eyebrow movement during speech in the Furhat robot.

So what implications does this have in the real world? Well, we know that there are many potential applications of social robots that involve noisy environments: schools, shopping malls, airports and train stations to name but a few, where the ability to see the lips can make a tangible difference.

But perhaps more importantly, given how sensitive we are to lip movements in connection with speech: A robot with proper visual articulation will allow us to suspend our disbelief for a little longer. Yes, of course we logically know that it is merely a machine, but if it looks and acts coherently like a character we can still allow ourselves to be carried away for a bit and engage in non-verbal interaction, on a level beyond factual information transactions. After all, that’s what social robotics is all about.