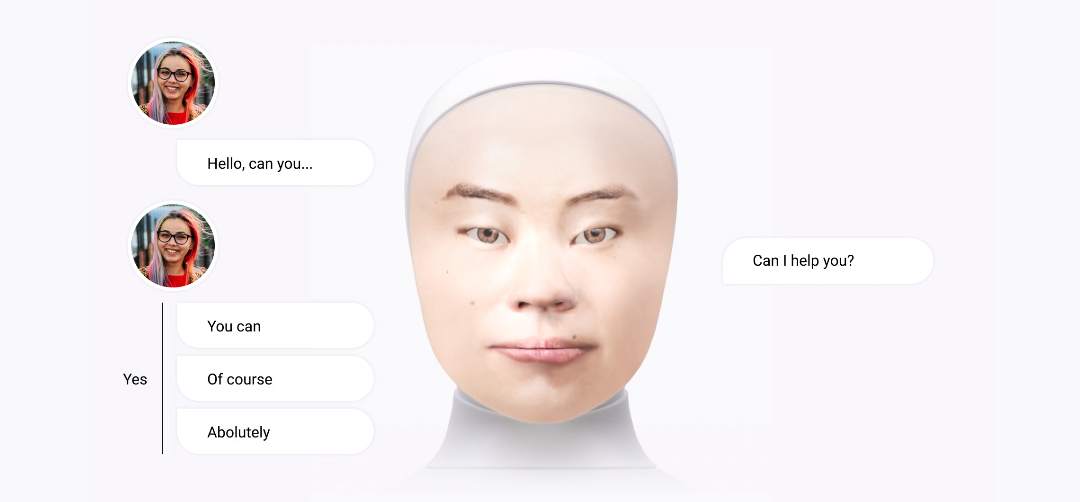

So, in essence, you could say that a social robot is a user interface, a new way for us to interact with machines that is similar to how we communicate with each other: through face-to-face conversation.

While this form of interaction is potentially more powerful and intuitive than traditional user interfaces, since we learn it already as children and use it every day, it is also technically challenging to construct such a machine. This is known as Moravec’s paradox: Tasks that are hard for humans (such as calculating 345×827) are very easy for computers, whereas tasks that are easy for humans (such as peeling a banana or understanding a joke) are extremely difficult for machines. Nevertheless, recent advancements in AI now allow us to have face-to-face conversations with machines in a way that was impossible just ten years ago.

In this blog post, I will argue why social robots such as the Furhat robot allow for more natural interaction with machines, and explain the technical solutions that allow Furhat to have conversations with humans.

Are you there?

When I talk to my smart speaker or the voice assistant on my smartphone, it feels like I am talking to someone who is not present with me. To initiate the conversation, I have to use a “wake word” (like “Hey Siri”) or press a button. The assistant does not know whether I am there, so it would not be able to initiate an interaction with me. Also, it never knows whether I am still in the room, so I will have to keep using the wake word for every turn in the conversation. Contrary to this, a social robot can see people around it and figure out whether they are still engaged in the conversation or not. As humans, we also intuitively understand this: it feels natural for us to walk up to the robot and look at it when we want to talk to it, and when we disengage, we naturally walk or look away. This allows for a much more natural interaction.

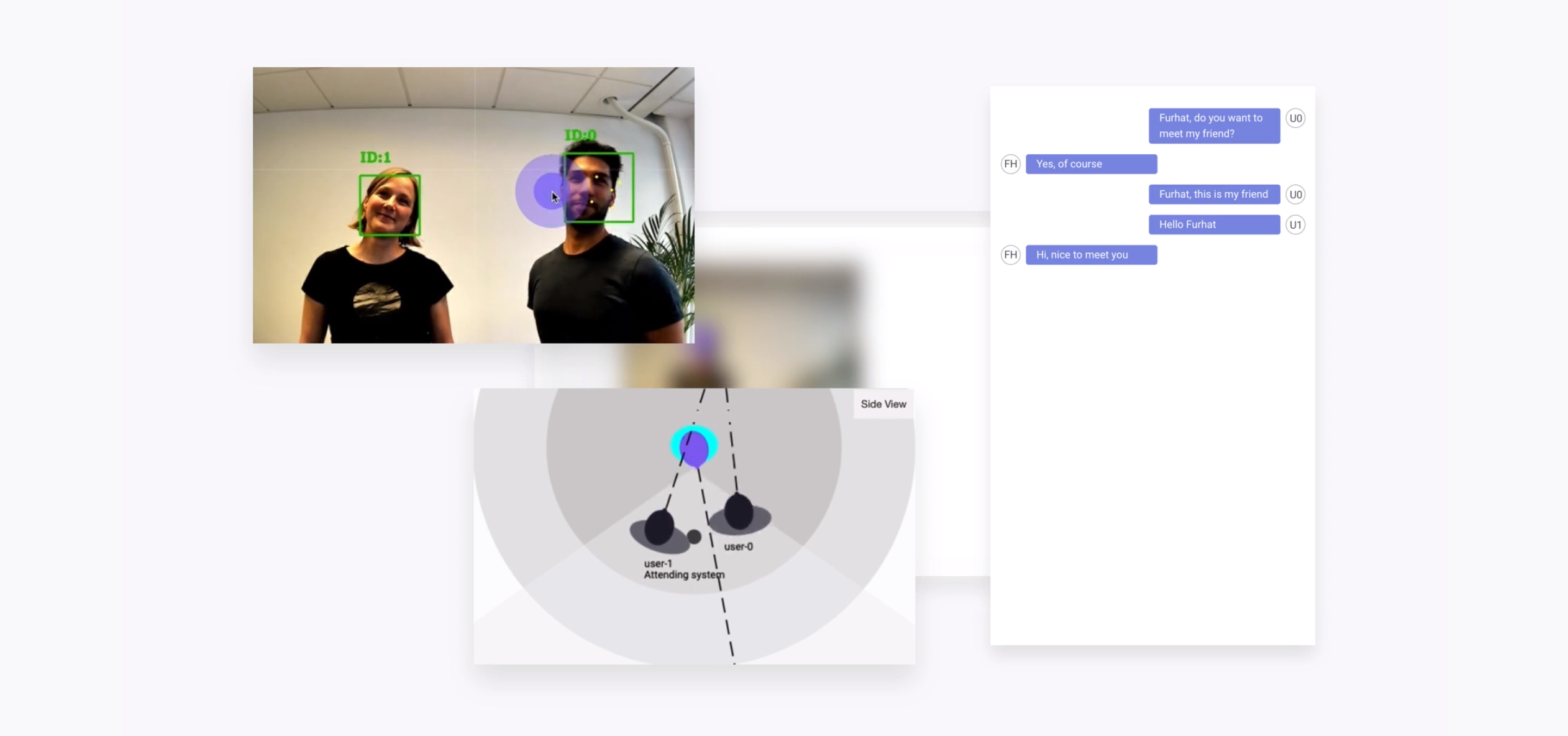

Social robots typically keep track of people in their surroundings using a camera. Unlike humans, who use their eyes to see, Furhat’s camera is fixed in the chest, but is wide-angle, so that many people can be tracked at the same time. Thanks to recent advancements in machine learning, Furhat has a very robust face detection software, which also works in low-lit conditions. Using face tracking algorithms and face recognition software, Furhat can track the movement of these faces from frame-to-frame without mixing up the individual users. This information is then combined to create a so-called situation model, which keeps track of the different users that are engaged in the conversation, as well as bystanders who are not engaged, and helps the robot to know when someone is entering or leaving the interaction. (For privacy reasons, face tracking and recognition are only processed locally on the robot, and data is not stored long term).

Since a social robot has a clear idea of when the conversation starts and ends, we can provide a much more fluent interaction experience, with more rapid turn-taking, than what is possible with a voice assistant.

The power of conversation

To understand what the user is saying, the robot needs to do speech recognition, which translates the user’s speech to text, and then natural language understanding, which translates this text to something that is meaningful to a computer. In essence, Furhat extracts the overall intent of what the user says (as being for example a Greeting, a Request or a Statement), as well as pieces of information called entities (such as a time, a date or the name of a city). Since there are many ways of saying the same thing, the developer needs to “teach” Furhat to recognize intents, by providing examples of what, for example, a pizza order may look like. Then, machine learning is used to train the robot on these examples, so that it may recognize the intent of a new utterance.

However, in a conversation, much of the meaning of what is said is not determined by the specific words used, but by the context. This makes conversation extremely efficient. If I would take an utterance out of context, such as “tomorrow”, you wouldn’t be able to tell what my intent is. Thus, the robot also needs to keep track of the current dialog state (i.e. the current context of the dialog). One way of keeping track of this is to use so-called state machines, where the conversation is always in one specific state, and expects the user to say something related to that state. For example, after the robot has asked “Do you want to pay by credit card?”, the user could be expected to say “yes” or “no”. However, in a real conversation, we are not constrained to follow such expectations, we could also say “do you accept Mastercard?” or “actually, I would like to change my order”. To handle this form of mixed-initiative dialog, Furhat keeps track of multiple dialog states at the same time, through the use of hierarchical statecharts.

Another key feature of social robots is the ability to interact with several people at the same time.

Are you talking to me?

Imagine two people booking tickets at an airport at the same time, or a social robot teaching two students a new language in a collaborative setting. This is not feasible with a voice assistant, as it would not be clear who is addressing whom. Even if you would have an animated agent presented on a screen, multi-party interaction becomes problematic, as it is not clear whom the agent would be addressing (think of a newsreader looking into the camera: everyone in the room thinks that they are being addressed).

The reason we are able to have effortless multi-party interaction with each other in physical face-to-face settings (but not over conference calls) is that we can so easily monitor each other’s gaze directions. This means that a social robot should have two important features: first, some means of monitoring users’ gaze direction to infer where they are directing their attention and whom they might be addressing. Second, it should be clear for the users if the robot is looking at them, the person standing next to them, or at some object in the shared space. Again, this is only possible if the robot is physically present.

In addition to tracking the location of individual users, Furhat tracks their headpose, which is a fairly reliable (but not perfect) indicator of their gaze direction, and is thereby able to infer whether the user is attending to Furhat or somewhere else. Through the use of multiple microphones, Furhat can also detect from which direction speech is coming (just like we have two ears to accomplish the same thing). Since Furhat can move its head (using a mechanical neck) and its eyes (using facial animation) independently, it can also quickly shift its attention between the users. Using the camera and face tracking, Furhat can move its head and eyes to maintain eye contact. These things combined make Furhat especially well suited to engage in multi-party interactions, unlike other conversational interfaces.

Non-verbal communication

Apart from being able to read and understand each other’s attention (through the direction of our gaze), the face is of course very important for expressing subtle cues, like raising the eyebrows, or smiling. These things are not just “icing on the cake”, but help to coordinate our interactions and may help to explain why we prefer to speak face-to-face. When you tell a story to your friends, you can immediately monitor their reactions while you are speaking, and you can use facial expressions to highlight certain words in your story and express your emotional attitudes.

This is clearly one of the key strengths of Furhat (compared to other robots), since the facial animation allows the robot to communicate these things in a subtle, but very expressive, manner. As humans, we react automatically to these signals – it is not something we have to learn. But it is of course also important for the robot to detect those signals. Through the robot’s face tracking software, it can detect when the user is smiling. This could for example be used to let Furhat return your smile, or allow a robot comedian to detect if the user thought the joke was funny.

Conclusions

To sum up, social robots are beginning to learn the things we appreciate with face-to-face conversations.

Of course, as humans we do have a lot of social skills that robots do not yet have, and so we might still prefer to talk to a human, if that option is available. But in many cases, talking to a human is not an option.

There is for example typically only one teacher in a classroom, who cannot give individual help to everyone at the same time. If you are in a hurry at an airport and need help, there might not be a human around to help you. And there might even be situations where you will prefer to talk to a social robot that will listen patiently without judging you – something humans are not always very good at. In those cases, a social robot might be a better alternative, that is closer to the experience of talking to a human, than a touchscreen or a voice assistant. And we should remember that we are only at the beginning of this journey towards socially intelligent robots. Given the advances in technology we have seen in the last decade, it will be very exciting to see what social skills robots will master in the coming years.